In this series blog, I’ll be discussing the boy heroes who helped shape Sebastian Duffy. Some are literary others televisual; the majority are British, yet there are outstanding exceptions; some are historical, most are contemporary; some are classically heroic – engaging in ripping yarns of derring-do, others are domestic, their heroics confined to the humdrum of boyhood; all communicated an infectious sense of adventure and anarchy I longed to emulate as a child. Surprisingly, many share another trait: they are boring individuals, underdeveloped and two-dimensional. It is often not the boy hero, himself, who is interesting, but the characters and action that unfold around him. He is the eye of the storm, the author and the reader, someone we can identify with and aspire to. All are mined from the same sparkling vein of boy heroes and had, by the time I began to take notice of them, been immediately preceded by several illustrious forebears; Just William and Billy Bunter pulsed faintly on my radar, Molesworth and Jennings did not.

tintinadulation: the tinkling of joy on discovering a previously unread Tintin book

Have you ever experienced a recurring dream where you discover a new Tintin book? You have? Then you are in good company. The boy reporter of indeterminate age is possibly the greatest young hero in literature and his adventures hold a special place in my heart. Even Hergé wasn’t sure how old he was suggesting 13 or 14 in the Soviets era, a few years older at the end. The world, meanwhile, had aged inexorably. Hergé employed a floating timeline, a literary device used notably in the 007 series.

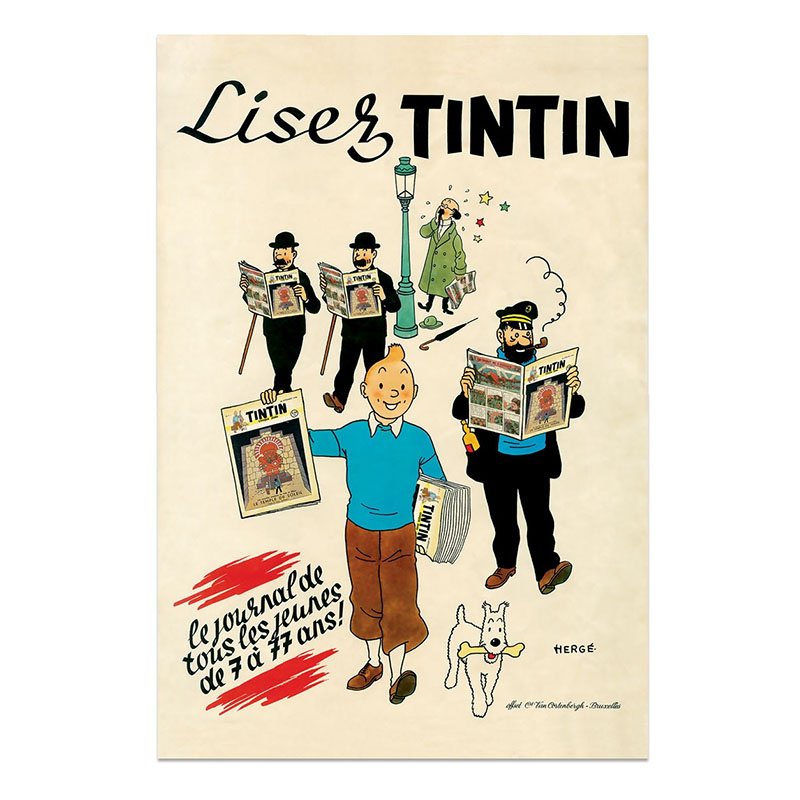

As a child, I was unaware of the political controversy surrounding Hergé: the anti-socialist propaganda of Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, the colonialist racism of Tintin in the Congo and the anti-Americanism (and, paradoxically, condemnation of racism) of Tintin in America, indeed the first two books were unavailable. In fact, as a young child, I was not exposed to the books at all; it was the television series Herge’s Adventures of Tintin that transfixed and transported me. Here was this boy, living without parents, not going to school, embarking on all sorts of adventures in exotic locations, sailing seas, climbing peaks, crossing deserts and trekking through jungles. He could punch out villains, fire a pistol, fly helicopters, steer a submarine… command a spaceship! It wasn’t until my teenage years that I got into the books. They retained the leitmotif of fairytales – rotters get their comeuppance – and the storylines were as fresh and bright as the ligne claire style Hergé perfected. Later, when I became aware of controversies, my conscience was assuaged by the knowledge that Herge’s views had evolved from the right-wing stance prevalent in middle class pre-war Belgium to an anti-Imperialist, left-leaning one.

The entire series has long-since been devoured, read and re-read, as have books about Tintin (Tintin by Michael Daubert set aside for Xmas), yet the rapture of my childhood – the tintinadulation – has been rekindled by my son, Sebastian, at eleven as keen a tintinologist as you’ll find. And so, a new set of Tintin books has appeared on the shelves (and the entire set of Blake and Mortimer), and posters, postcards and figurines fill his room, a 72cm resin rocket pride of place.

It was his passion for Tintin that led me in search of the films. The original TV series (Herge’s Adventures of Tintin) was made by Belvision between 1957 and 1964. The Broken Ear and King Ottokar’s Sceptre were made in black and white, a further eight were serialised as five-minute colour episodes – the ones I watched as a child along with other treasures like The Flashing Blade, Belle and Sebastian and Robinson Crusoe. It wasn’t until I rewatched those early Tintins recently that I realised how far the plots deviated from the books; little wonder my sense of newness reading them for the first time. Here’s episode one from The Broken Ear:

And here’s the Crab with the Golden Claws in it’s entirety (double length episodes)

The TV show most are au fait with is the Adventures of Tintin (1991-92), a Franco-Canadian collaboration featuring 21 of the books, each adhering to the original plot. I became so used to the voices on this series, that it took a while for the earlier ones to connect with my childhood memories, though nothing can beat the original title intro for inducing Mexican waves of nostalgia.

The two live action films are delightful curiosities. Tintin and the Golden Fleece (1961) and Tintin and the Blue Oranges (1964) are both live action, featuring Herge’s friend Jean Pierre Talbot as Tintin. Haddock was played by Georges Wilson in the former and Jean Bouise in the latter. Both are compelling and bring something unique to the role, though Bouise’s Bouduesque misanthropy ultimately grates and Wilson wins out for me. There are few examples on Youtube, though the films are cheap to buy. This first clip from Tintin and the Golden Fleece is a wonderful cinematic depiction of Tintin’s globetrotting.

Only a brief clip of The Blue Oranges is available out there:

Belvision went on to make two feature length films. The first, Tintin and the Temple of the Sun (1969) was based on The Seven Crystal Balls and Prisoners of the Sun. It has an excellent score by Francois Rabois, long-time collaborator of Jacques Brel. Unlike the TV series, Belvision stuck pretty closely to the books on this one. The opening of the film is excellent, and Sebastian was sure he spotted Bianca Castafiore in the audience. The other striking thing is Tintin’s peculiar voice, at least in the English version. It as if the actor due to voice Tintin fell ill and they used the person playing Calculus instead. This time, we have Vimeo to thank for making this otherwise relatively obscure film easy to source:

The second film, Tintin and the Lake of Sharks (1972), was written by a friend of Herge’s and features the usual cast, with Rastapopoulos as the villain. It is pleasant enough, but lacks Herge’s magic in much the same way the posthumously completed book Tintin and Alph-Art does. Here is the complete film:

The last film made, of course, is the Spielberg/Jackson version, Tintin and the Secret of the Unicorn, a surprisingly faithful adaptation of several books (The Crab with the Golden Claws, The Secret of the Unicorn and Red Rackham’s Treasure), which captures the thrill of the originals, but not the soul; a well-meaning, entertaining, but dead-eyed pastiche. The next film, reputedly based on Prisoners of the Sun isn’t due out until at least 2021, if at all; the modest return on the first imperilling its progress.

I have saved the most delightful film until the end, although it is the earliest of them all. Made in 1947, when Hergé was only 39, it is a stop-motion puppet production of The Crab with the Golden Claws. It is so rare that only one copy is believed to exist, preserved at the Cinémathèque Royale in Belgium and available for private screenings only to members of the Tintin Club. Luckily for us, it is now available on YouTube, albeit in French. Heaven.

In the next blog, I’ll be discussing another boy hero of my youth. I’m off to watch Blue Oranges with Sebastian and Violette before bedtime. They’ve yet to dream of unwritten Tintin books, but I’m sure it won’t be long.